What Is Going on With Frank Lloyd Wright’s Freeman House?

- KP

- Sep 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Frank Lloyd Wright’s landmark Freeman House is the smallest of his four textile-block homes in Los Angeles, yet it is the greatest preservation failure. How did this happen?

Samuel and Harriet Freeman commissioned the architect in 1924 after visiting her sister Leah Lovell, a teacher at Hollyhock, the home FLW built for Aline Barnsdall on Hollywood Boulevard. But what was supposed to be a three-month project worth $10,000 ballooned to $25,000 over thirteen months.

”Sam and I would come up at the end of the day to see what had been accomplished and the workmen would just laugh,” Harriet recalled to the Los Angeles Times in 1984.

”Our friends thought we were crazy when we started building this house,” added Samuel Freeman, a jeweler, in a previous 1965 interview. ”Several carpenters actually walked off the job, because they didn’t like the look of it. No one understood what Wright was trying to do.”

But the Freemans did, and their trust (and patience) ultimately paid off, believed Samuel. “I think the success of the place was because I didn’t give [Wright] any suggestions.”

In May 1925, the Freemans moved into their hillside residence, comprised of 12,000 16-inch concrete textile blocks that had been mixed with sand from the Glencoe Way property.

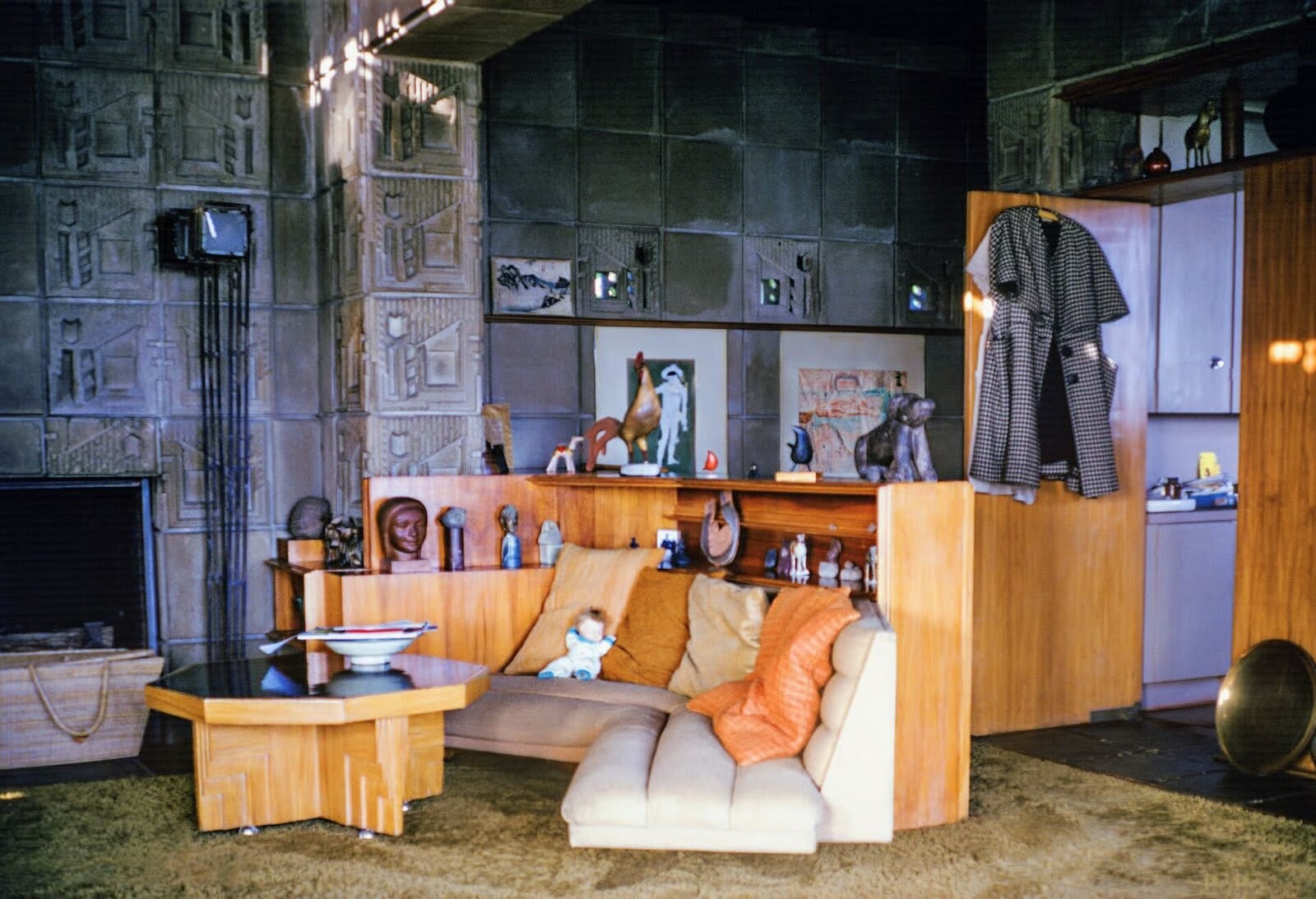

On the street level is an entrance, kitchen, combination living-dining room with oak flooring and a south-facing balcony offering a bird’s eye view of the Hollywood Boulevard-Highland Avenue intersection (pictured above).

The lower level of the home features the living quarters: two bedrooms, a bathroom, lounge, and storage/laundry room—all tucked away into the hillside.

The west and east corners of the south elevation, looking down at Hollywood Boulevard, were formed by mitered glass that spanned both stories (see photo below). The Freeman House remains significant for being Wright’s first use of mitered glass corners.

From the beginning, there was a serious structural issue: the blocks absorbed water and when it rained, the roof leaked. Tired of living amongst pots and pans collecting droplets, the Freemans brought in FLW associate Rudolph Schindler to make necessary alterations. He added metal flashing to prevent seepage—which angered FLW when he came to visit. “What have you done to my house?” he demanded. Then got in his car and drove away.

At the time the Freemans were perplexed, but years later FLW revealed why he had been so upset when Harriet visited his Wisconsin home, Taliesin East. “But he was charming,” she remembered in 1984. “Everything about Mr. Wright was likable and human.”

In addition to fixing the leaky roof, Schindler built custom furnishings for the living room, dining room, and bedrooms, all of which replaced the cardboard boxes utilized by the couple who had gone broke building their dream home.

Schindler also transformed the storage/laundry room below the garage into guest quarters, which the Freemans rented out to a host of prominent tenants: Paramount director Jean Negulesco, bandleader Xavier Cugat, actress Helen Walker, writer Henrietta Lichtenstein, and World War II veteran Norman T. Byrne. In 1934, a lesser-known boarder, 28-year-old Hilary Lynn, made headlines when she fainted while driving and crashed her vehicle into a light post down the street in the 1900 block of Hillcrest Road.

The avant-garde Freemans envisioned their artistic home as a cultural center for the community. It was a gathering place for creatives of all types: film, dance, literature. In the 1950s, they took in actors blacklisted during the Red Scare.

Samuel and Harriet eventually separated, yet both remained in the home, with Samuel residing in an apartment with kitchenette that Schindler created from the west bedroom. Harriet, a dancer and teacher, traveled extensively in the summer months. “The privilege of returning to California at the end of a vacation was a joy, but imagine the joy of coming back to a Frank Lloyd Wright house,” she told the LA Times. “It affected my whole life.”

Samuel and Harriet both died in the living room, five years apart. After a stroke left her bedridden, she chose to spend her final months in 1986 gazing upon the Hollywood view she had known for sixty-one years.

“She has watched the city change from the house’s horizontal corner windows and through the cut-outs in the leaf patterns of the concrete blocks,” Diane Kanner wrote in a 1984 Times piece about Harriet’s decision to bequeath the home to the USC School of Architecture upon her death (along with another $200,000 for upkeep). Harriet passed away on February 18, 1986, two days after her 93rd birthday.

Stewardship of the historic home immediately proved too great a responsibility for the university. In 1988, USC reported the foundation was sinking and much of the concrete had deteriorated. To raise funds, professor and Freeman House director Jeffrey Chusid, who lived in the residence, organized a project that allowed FLW admirers to purchase a $250 concrete block made from one of the original molds. In 1992, the house was opened to the pubic for tours at $10 a pop, with proceeds going towards a proposed $1.6 million restoration project.

Two years later, the home was further damaged by the Northridge earthquake, yet not immediately repaired due to a years-long disagreement between USC and the Federal Emergency Management Agency: The university requested $3.6 million; FEMA offered $852,000 ($1.9 million today).

All the while, Chusid reportedly continued to live at the Freeman House, until 1997 when he left USC for the University of Texas-Austin. The following year, the LA Times published a scathing commentary titled “Wright, Done Wrong” that minced no words.

“Today, the house is a conspicuous object of neglect,” blasted Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff. “Neighbors—who say they have waited more than a decade without any visible improvements to the house—complain regularly that the building is an eyesore and that the school has done nothing but make false promises about its rehabilitation.” (Ironically, in 2011 Chusid authored the book Saving Wright: The Freeman House and the Preservation of Meaning, Materials, and Modernity.)

By 2000, USC had accepted FEMA’s offer of $901,000 and with another $500,000 from donors planned a stabilization project as a prelude to a larger cosmetic restoration (which reportedly did not happen.)

“I lived in Schindler’s neighboring DeKeyser house during the earthquake repair years,” designer Tim Champ tweeted in 2019. “The Freeman house was often left open and unsecured. I’m surprised it wasn’t completely looted or worse.” In a follow-up interview with Curbed, he continued: “I would go by there myself and the front door was wide open.”

During this time, all of the furnishings were removed from the home and put in USC’s storage facility, a former LADWP power plant located downtown. Unbelievably, in 2012 four custom pieces worth over $200,000—a pair of FLW floor lamps originally designed for the Storer House; a cushioned chair and tea cart both by Schindler—went missing, yet no one at USC reported the crime to police.

It wasn’t until a whistleblower sent an anonymous tip to the Times in 2019 that the heist finally came to light. USC initially denied it, but an LAPD investigation proved otherwise. “A former USC associate with knowledge of the storage room’s contents who asked to remain anonymous tells Curbed that the theft was well-known to people at the school at the time, and that no photos have been shared because the school does not know exactly how many pieces have disappeared,” Curbed reported in February 2019.

Weeks later, LAPD released photos of the priceless items and asked for the public’s help in recovering them. But as of 2025, it all remains missing.

In July 2021, USC finally put the Freeman House on the market. The following February, the school sold the property to former graduate Richard Weintraub for $1.8 million, a fraction of the $4.25 million asking price. The house “has to live the way it lived—it was a salon for intellectual passions,” he boasted to the Times.

Three-and-a-half years later, the Freeman House continues to live as it has for decades, in complete disrepair, except now it looks more derelict than ever (compare the 2022 photo above to the 2025 photos in the gallery below).

Eroding away behind a chain-link fence, the historic home is surrounded by construction materials that have been left to the elements since last year (photos below were taken in September 2025). LA Department of Building and Safety approved Weintraub’s restoration plans back in May 2024—sixteen months ago, and yet there is still no progress.

(Weintraub did not reply to an email seeking comment on the future of the Freeman House.)

I was given a tour of the interior back in November 2023 by the general contractor in charge of renovating the house.

I asked how long it would take to complete the restoration. He told me at least 2 years.

I live in Ottawa Canada. I told him I’d be back to see the house in two years. Looks like I’ll have to postpone my visit.

I go to this sight every day hoping for a new story. No pressure lol